Update: This is the most popular post on my blog, and I’ve found that in the two years since I put it up, the original YouTube video (with better sound quality) has been removed and the Essential Dissent site is cleared out. I’ve tried to fix it up as best I can.

I watched the video below of Paul Mason‘s speech at the Left Forum 2011 Opening Plenary and was flabbergasted. It’s packed with incisive analysis of our current historical moment. I couldn’t find a transcript, so wrote it up myself. For more, see what used to be Essential Dissent.

Hey, if you’re gonna do your internationalism, I think, you know, inviting a white guy from England, you could do better. [laughter]

Now, as a public service journalist, I’m required not to have public political opinions. For the right to go and interview, loyally and inquisitively, the opposite of this, something like a Tea Party gathering. I guard that jealously, so I’m obliged to say to you, don’t take it personally when I say my presence here is not designed to indicate support for any Left party or program in America. Okay?

As a labor historian, my book is a narrative history of the global labor movement, with comparisons to now. It is fascinating to watch a piece of labor history unfolding. Now, we are in the middle of a wave of discontent. In some countries, revolutions; in some countries, social upheavals – Rick listed them – in others, the revival of student and labor activism on levels not seen for a generation.

In my profession, we’ve struggled to understand this. I’ve covered the strikes and protests in London, in Southern Europe, the crash and burn of a party that ruled Ireland for 90 years. I’ve become, for those who manage to watch British TV, something of an anti-Glenn Beck, in the sense that, though I haven’t been to Egypt, my job is to go in the studio with a map of the Middle East and explain to people things about why contagion happens.

My bosses asked me quite suddenly, because they’d suddenly got a big interview with somebody about the whole revolutionary wave about a month ago, “Paul, please come in immediately, and start making a program about the process of revolutionary contagion.” I said to them, “Where do you wanna do the pieces to camera?” My producer said, “Well, the British Museum turned us down, so why don’t we go to Karl Marx’s flat in Dean Street, Soho. And take a globe and hang it out the window there.”

So look, I’ve sat with mainstream journalists, old hands of the Cold War, who are no friends of gatherings like this, or your agenda, and we have pondered the question “Is this February 1917?” together in our newsroom, the newsroom of a major, serious, global network.

Now there are, of course, parallels with many revolutionary situations and waves. There are elements of 1848 in this, for sure; there are echoes of 1917 in Egypt already, as the workers are finally allowed to carry out their economic struggles, and as the democrats, who made that revolution, start asking themselves what that one chant for social justice would actually mean. There are elements of May 68 in what’s happening to the students. But I want to try to focus on what is new in the situation.

Background

Let’s establish what we’re talking about. In July 2009, the youth of Iran rose up in the Green Wave against the theft of the election [smattering of applause] – it’ll be a long list if you carry on clapping. It was called a Twitter revolution. In December 2009, there was a youth uprising in Greece against the police killing of a young protestor. All the rest of the next year has a been a cycle of general strikes, Molotov cocktails, political crisis in Greece, part of the Euro Zone – for now. By October 2010, all over France, French students joined workers on the streets, and youth from the banlieues – youth from the projects – on the streets together, for what?

Well, this is my favorite press cutting of the last 12 months – Associated Press, 19th of October 2010.

Masked youths, clad in black, torched cars, smashed storefronts, and threw up roadblocks Tuesday, clashing with riot police across France as protests over [pause] raising the retirement age to 62 [laughter] took a radical turn.” [more laughter]

Then, in November, British student demos and occupations began, trashing the party HQ of the Conservatives, leading to some 60 colleges, including all the big-name global universities, the Harvard and Yale equivalents, and Princeton equivalents – you know, Cambridge, LSE, UCL – occupied.

And then Mohammed Bouazizi set himself on fire in a small town in Tunisia. And you don’t need to be told the rest. It doesn’t need to be added. Madison.

Today, there are Saudi and Qatari tanks on the streets of Bahrain. There is an escalating military situation over Libya. There is an escalating diplomatic situation among Shi’a in the Middle East about this Bahraini crackdown. So a tiny country has a potentially detonating effect. There are live-fire clashes on the streets of Yemen. There are in Syria three towns today, those of you are not like me and Laura, on this perpetual news cycle, is it only today that Syria blew up, with three towns experiencing the shooting of protestors.

Now my job is to try and explain this. And, in the story, I’ve noticed three things happening that are new and I’m going to try to talk about them. The demographics, the technology, and the behavior.

Demographics

Ok, in demographics – Rick said it – you’ve got youth without a future. In North Africa, you’ve got 20% youth unemployment, but in countries where two thirds of the population are below the age of 30. In Europe and for a layer in the Middle East, a crucial layer that helped start these revolutions, you have a more specific thing – that is, the graduate without a future.

For both sets of people, the economic crisis that began with Lehman Brothers was not just some downturn. Not just a blip as the economic person within the US Embassy in London assured me at the time. It has turned the entire curve of their life upside down. Their curve was upwards. Do this, you’ll get a better life. Now they can only see their lives getting worse than those of their parents.

And, just to add, both in North Africa and in peripheral Europe, these economic crises raise crises of political legitimacy. Obviously in a dictatorship, but also remember, Southern Europe is taking the medicine dictated by Germany. When I reported from Athens, some of my viewers were shocked to hear me say, that if you go into the mountains and small towns of Greece, you will meet people who lived under German occupation. Now whatever your position on World War Two is and whatever your nationality, you have to understand what it is for them to lose their pensions because Germany says so. Watch what happens.

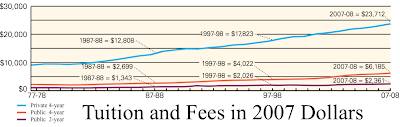

Now, for those who are my age, this idea of a graduate without a future, or a graduate workforce that suddenly faces a doom scenario can be easily misunderstood. In my generation students had a liberal education, we didn’t pay for our education, we had a lot of time, we didn’t have to work, and we got jobs. Now, students are a key part of the workforce. Their casual labor keeps the coffee bars going, the cocktail bars going. They are part of an education industry, some tens of billions of dollars’ worth in the world. It’s a straight swap: you pay this, you get this commodity called a degree or a higher degree. They’re pretty crucial to the financial system: Citigroup alone made $200 million from its student loan book in 2007. They’re tested to within an inch of their lives, every month, every year. The jobs they get are like indentured labor. “Wow, you get a job for a consultancy firm. I only have to stay with them for three years.”

Their life was going to be better, and now it looks like it’s going to be worse.

It’s clear that the austerity programs that are being heaped on top of the original recession that followed Lehman – and in this regard, Madison is a harbinger for you, we’ve already got it in Europe, and the rest of the world has the austerity. We are finding three sets of people who it’s affecting. This graduate workforce and students, the urban poor, and the organized working class.

But what’s new? Well, 20 years of neoliberalism have taught these people, all three sets of them, to be individualistic. To have what the sociologist Richard Sennett calls “weak ties” to each other – and to organizations, weak ties to their organizations, even weak ties to their own company. Neoliberalism created, as Sennett writes, an ideal worker, who he describes like this: a self oriented to the short term, focused on potential ability rather than actual skill, willing to abandon past experience, with weak institutional loyalty, low levels of trust, and high levels of anxiety about their own potential uselessness as capitalism changes.

They are the opposite of the worker in the Weberian sociological pyramid, in the hierarchy diagram. They work in networked organizations, their work is networked, their leisure is networked. They’ve begun to struggle using networks.

Of course, each country has its own mix. The size of the urban poor, the radicalism of the student movement differs in every country, but I think, what I’ve noticed as I’ve reported on this, in many of the countries, the social mix is now a lot more like that which created the Paris Commune, with a strong urban poor, a weaker organized labor, and a radicalized intelligentsia, than for example Flint, Michigan in 1937.

Either way, it all calls to mind for me, the warning of Taine, the historian of the French Revolution. I summarize: he said, when it comes to revolutions, don’t just worry about the poor, worry about poor lawyers. Because in the student, the lawyer, the civil servant, the doctor, the classics professor, starving in their garret, in their unattended waiting room, there’s a potential Jacobin, says Taine. Well now, in every garret, there is a laptop. And this is where technology comes in.

Technology

Of course, you’ll be sick already of this debate. Was it a Facebook revolution? The Egyptian revolutionaries think it’s an insult to call it a Facebook revolution. When they switched off the internet, they simply went onto the streets more.

But I stand on the side that says these movements are being expressed through and created by a new technological reality. But it’s not just, or even primarily, social media. Of course, Twitter, Facebook, yfrog, allow protestors to mobilize quickly, to present to the mainstream media – people like me – undeniable evidence instantly, which allows us all to become witnesses, again almost instantly, to acts of resistance and repression.

Who can forget the placard in Tahrir Square? “Mubarak, please go. My arms are tired.” Or who can forget on YouTube the bunch of older men in Tahrir Square chanting, “Condoleezza, Condoleezza, please give Mubarak a visa.” They hadn’t quite caught up with the career path of Condoleezza, but you can see what they were trying to say.

But it’s a lot of other things – it’s mobile telephony, it’s mainstream media leverage, it’s the sharing of cultural memes of resistance, the snatches of songs, the snatches of poetry, poetry chanted from the rooftops of Teheran during the crisis when you can’t go on the streets. It’s the constant photographing on cell phones, which says to soldiers and policemen, you will end up at the International Criminal Court, I add if your country has signed the treaty which represents it.

In the debate that’s broken out, Malcolm Gladwell famously says what’s wrong with social networking is that it can only achieve small things. It can annoy, embarrass, but it couldn’t have achieved what the Civil Rights Movement achieved. And for that, you need hierarchy to confront hierarchy. And I’m not hostile to that, but I think it’s more complex.

I think, if you study in detail what the April 6th Movement did, they didn’t just do social networking. They had a plan; a strategy, borrowed from Gene Sharp‘s famous strategy guide for non-violent revolution; they had a network, if you read the interviews, of cells, quite similar to the way guerilla movements organize. Fifty people with one leader, one leader knows the other leaders, but nobody else does.

The New Ideas of the 20th Century

What they’d learned, though, from the 20th century, was to try, in the beginning, to inure themselves to the hierarchical dangers of nationalism, of Stalinism, of Islamism, because they had read more than the generation I came from. They had in a way, as Foucault once said to Gilles Deleuze, you know we took a hundred years to understand class, we took to the 19th century to understand class, but it’s taken us another hundred years to understand power. If you go to a British student occupation, the books on the floor are Foucault, Deleuze, obviously Hardt and Negri, Chomsky. Those books weren’t – those ideas were not formulated in the student occupations of my early twenties.

In addition, what they learned practically from the anarchist and eco-warrior tradition, was the idea of creating spaces and that space is a conquest. The Tahrir Square organizers had learned this, that many of them had had experience of the Western students and eco-movement. And here I think they’ve begun to do what syndicalists did, from Lawrence, Massachusetts to Buenos Aires to Welsh coal mines. They started to recognize that between reform and revolution, there is another space for the expanded control over your own life, over place, over culture, over personal relationships.

The British students became so addicted to occupying, that even after the law was passed, they carried on occupying. A woman said after that vote was taken, “Great, my house is crap anyway. I’d rather live in an occupation than a student hovel.” But above all, they use these methods that drive union organizers and left group organizers mad – the lack of commitment, the constant febrility of what they do.

I think another product of the new technological reality is that propaganda is beginning to become highly flammable. Highly hard to make stick. Yes, you get spin doctors on Twitter, yes you get outright disinformation. But the truth acts like white blood cells, and it is more effective in a social media than a mainstream media. Mainstream media is good at creating bubbles where people can believe a partial version of the truth. Social media is good at popping the bubble. That’s all I claim for it, but I think you have to see it, and if you’ve seen it used, it is an interesting part of the new reality.

Finally, I think the technology is making the protests and as it were the vibe, which you described, Laura, – is making the protests, for the first time in 20 years, seem more modern than the methods of those who oppose them, whereas the old methods, the pure strike, the pure student demo, the pure intellectual thing, the pure riot by the oppressed, always were able to be pigeonholed.

Behavior

Finally I’m going to talk about – just for one minute – behavior.

André Gorz, is probably not the most popular person to bring up in the middle of American labor’s greatest upsurge for 20 years, but he did write a book called Farewell to the Working Class. I don’t agree with the thesis, but what he describes, in terms of a revolution, is very interesting. He said it’s first and foremost the irreversible destruction of the machinery of domination. It implies a form of collective practice capable of bypassing and superseding it – that machinery – through the development of an alternative network of relations. I think this is what we’re seeing from Teheran to Madison is the development of alternative networks of relations and means of struggle that represent the fact that the swarm, the disorganized mass, organized through networks, can sometimes, and up to a point, defeat the hierarchy.

Caveats

Of course that begs [sic] the question where do you go, when the hierarchy fights back? And this is the next phase, which I won’t offer any conclusions on, because my job is to simply report it. There’s a host of caveats – some places they can switch the internet off, some places the powerful are so strong because they have mass support – Iran, Ahmadinejad has a [garbled] militia of the poor, China the Communist Party is a 60-million-strong network, it functions like a network.

Creating the Space of Community

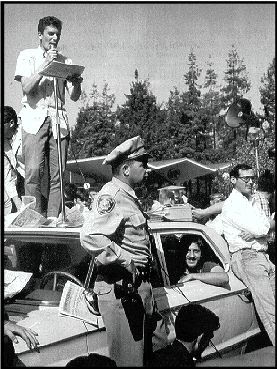

But I wanna finish, because I think these words do describe what is happening, with the words of one of the American student protestors. They’d gone into their college, and set up a stall, and the authorities didn’t like it and called the cops. And the cops came to arrest somebody, so the students sat down around the police car. And one young guy, 21 years old, took off his shoes, and stood on top of the police car, and made a speech, and began a mass meeting that lasxted for seven days. And later, he described what he’d felt. The act of sitting around the police car, of getting up on the car, and starting to speak, of physically structuring the possibility of a community, he said, all of a sudden, there’s a self-justifying factor to it. In a way, once it’s been established, there might be other reasons for sitting around the police car than keeping it from moving. Namely, participating in the community. “I have never experienced that, nearly so strong, as around the police car.”

Now those are the words of Mario Savio. [applause] And the act I’m describing was in Berkeley in 1964.

And you may have thought – and my colleagues and my profession may have thought – that such sentiments, such idealism, such ability to create the sudden community out of the empty space of isolated individuals, to achieve change through non-violence, and through eloquence – you may have thought that the days of all that were gone.

Well, they’re back.

People might want to come here from http://bit.ly/hPUD5M, bit.ly/hPUD5M, or bit.ly /hPUD5M. (Doing this so the pseudo-link on YouTube is searchable.)

LikeLike